At last. Despite being available in French, Italian, Chinese, Korean, and several other languages for a long time, the unofficial English version of arguably one of the greatest and influential manga series is finally done. I say done, but that’s not quite so accurate since Happyscans and I’ll be re-doing the first 6 volumes as well as fixing all the typos and mistranslations I’ve made (the updated versions will be labeled as v2 in my mega folder). Now I’ve been meaning to do a some-thoughts-post on Tomorrow’s Joe for a while now, and I believe now’s the best time for that. So if you don’t want to get spoiled or don’t care about my opinions, the download links are right below.

The 60s were an exciting time for Japan and its manga industry. The impact of the Korean War and investment in heavy industries of the 50s set the groundwork for economic recovery, and the 1964 Summer Olympics held at Tokyo demonstrated to the world that Japan had risen from the ashes. As the Japanese consumer became richer, the cheaper aka-hon and kashi-hon manga were quickly phased out, replaced by the weekly/monthly magazines that still dominate the manga industry today. Demand for manga not only soared, but diversified as the Dankai generation (baby-boomers born in the late 40s) entered adulthood and now wanted something more mature than what the mainstream offered. That alternative was gekiga, and in 1964, the establishment of the seminal magazine Garo gave it a strong voice through which it could communicate its ideas. Its poster-child, Kamui from Shirato Sanpei’s Kamui-den, was beloved by many college students across the nation. Garo’s success soon paved the way for the first “seinen magazines” to appear in the late 60s; Manga Action and Young Comic in ’67, Big Comic and Play Comicin ’68. But gekiga, or to speak more generally, “mature/alternative manga” were not restricted to these seinen or avant-garde obscure magazines. The management of the hugely popular Weekly Shounen Magazine, in the wake of the W3-incident of 1965 in which Tezuka angrily switched over to the rival magazine Weekly Shounen Sunday amidst accusations of plagiarism, decided to tap into the Dankai-demographic by allowing much more serious and mature stories to be told. And it was in Weekly Shounen Magazine that one of the greats in the gekiga-movement, the so-called “King of Gekiga” by some, would leave his mark.

That man is Kajiwara Ikki, the author of Tomorrow’s Joe (working under the pen-name Takamori Asao). In the late 60s, he wrote 3 of the most influential sports manga of all time AT ONCE: Kyojin no Hoshi (’66-71), Ashita no Joe (’68-73), and Tiger Mask (’68-71). One related famous anecdote is that Tezuka was so impressed by Star of the Giants (Kyojin no Hoshi) that he demanded his assistants to be able to explain precisely what made this manga so great. Indeed, Kajiwara’s absolute mastery at hot-blooded sports stories may have played a significant role in Tezuka’s decision not to try his own hand at the genre.

Although there’s no precise written-record about who’s responsible for exactly what elements in Tomorrow’s Joe, looking at the early works of Chiba Tetsuya and Kajiwara Ikki helps quite a bit. Kajiwara’s stories were known for their tense, hot-blooded mood featuring hard-working heroes who slowly progress their goals in a bitter 2-steps-forward-one-step-backward fashion, often resulting in a tragic end. Chiba on the other hand, preferred lighter-hearted stories though still spiced with a fair amount of hardships. Arguably, his only real grim work prior to Tomorrow’s Joe was Shidenkai no Taka, a WW2 flying ace story partly based on a true story of the Japanese aces of the 343rd Naval Air Group flying the new N1K (shidenkai) fighters in the closing stages of the Pacific War; Chiba would later consider this manga a failure for its overt seriousness despite being well-received. But if the harsh and bitter elements of Tomorrow’s Joe is more attributable to Kajiwara than Chiba, then Chiba was heavily responsible for one of manga’s most iconic characters, Yabuki Joe. In the works leading up to Joe such as Harisu no Kaze or Missokasu, Chiba had been developing his own version of the archetypical rough-and-tumble delinquent. In fact, it was Chiba’s experience in drawing the boxing-arc for Harisu no Kaze that would spur him into doing a series solely about boxing.

Now before I comment on Chiba’s art in Tomorrow’s Joe, I must confess I have a pet peeve with the term “dated.” I often see this term used in comments for famous manga of the 60s and the 70s. True, they are “dated” in the sense that few, if any, modern-day mangaka would still draw in that style. However, what irks me is when people necessarily equate “datedness” as a negative attribute. For instance, “Oh, manga X has a really dated art but the story still holds up so you should read it!” But it really shouldn’t be used in this negative manner unless the said “dated art” inadequately depicts the scene, mood, or emotional state of characters. This is why I stay far away from this term when describing the art in Tomorrow’s Joe, which I never felt was inadequate. In fact, instead of judging it from today’s perspective on how dated it is, I think it’s far more interesting to judge from a 60s perspective on how forward or novel it was.

![]() |

| Tetsujin 28 (’56-66) and Sasuke (’61-66) |

Here, you have Yokoyama Mitsuteru’s Tetsujin 28 on the left and Shirato Sanpei’s Sasuke on the right. Both series were serialized in Shounen throughout the early 60s. You can see both mangaka are carrying over the mainstream art-style of the 50s heavily influenced by Tezuka. Simple and clear depictions of motion, cartoony limbs, minimal detail, and not much variation in the linework.

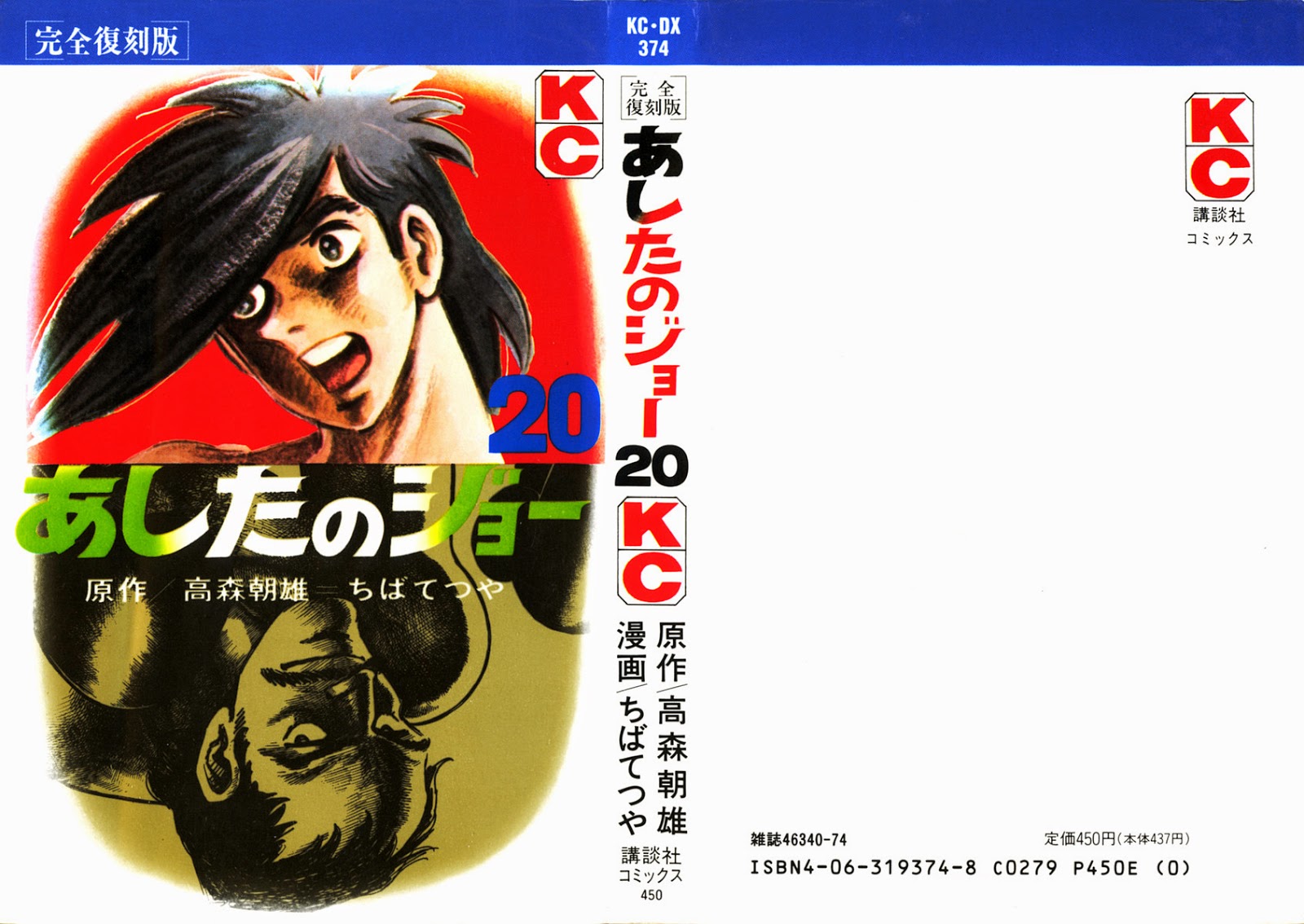

![]() |

| Fantasy World Jun (’67) |

Now these are from Ishinomori Shotarou’s experimental work Fantasy World Jun which serialized in COM, Tezuka’s answer to Garo…

![]() |

| Chikyuu wo Nomu (’68) |

while these 3 images are from Tezuka’s Swallowing the Earth. Serialized in the seinen magazine Big Comic, I believe it’s considered Tezuka’s first attempt at gekiga. When you look at these manga, one of the things you’ll notice is that they’re trying to break away from the ’50s mold with much more innovative or surreal paneling, and putting a lot more detail in objects and backgrounds. In fact, Tezuka’s background is so detailed that his simplistic characters stand out in stark contrast. These characters were hardly different from their earlier, more mainstream counterparts. Indeed, a character from the earlier Magma Ambassador could inconspicuously sneak his way into Swallowing the Earth and vice-versa. The same goes for Fantasy-World Jun. The character’s faces, hands, and other body parts don’t have any substantial detail, nor are they drawn in realistic proportions. Now this is not to criticize or belittle their artwork, which I both admire. But it is quite telling of the mindset of a mangaka working in the early and mid-60s. Perhaps they felt that realistic-looking characters just weren’t appropriate for the medium, or that people just weren’t ready for it yet. Whatever the reason, the point is that mangaka, whether consciously or subconsciously, weren’t quite comfortable in giving realism to manga characters even as they strove to evolve their artwork to the next level.

![]() |

| Kamui-den (’64-71) |

Now enter Garo and Shirato Sanpei’s Kamui-den. You can immediately notice that this is nothing like the art posted so far. The linework no longer have that simple and squeaky-clean look as in Shirato’s earlier Sasuke and the characters have lost their exaggerated cartoony curves.

This style quickly spread in the gekiga-scene and in the 70s, you would get works like Kojima Goseki’s Lone Wolf and Cub, whose artwork still impresses readers today.

Now let’s turn our attention to Tomorrow’s Joe. From this page and most of volume 1, you might think that there’s nothing really avant-garde or innovative about Chiba’s art. And you’d be right. Stylistically, it’s certainly a lot closer to the mainstream manga under Tezuka’s shadow than something like Kamui-den.

![]() |

| From vol.1 |

But then towards the end of volume 1, you notice that Chiba is not going to be retreading same grounds. Just look at how the bodies are drawn. There’s actually some hatching to give shape to the muscles! Joe has nipples! And holy shit, there’s even a faint trace of nostrils in the bottom left panels! “Wooooowww… So a few lines, unsexy man nipples, and a poor excuse for a nostril is enough to excite you?” Go back and flip through mainstream 50s and early 60s manga if you’re thinking this. Go back to Fantasy World Jun and Swallowing the Earth, which I posted examples of above. Keep in mind that those are two experimental works running in a magazine aimed at young adults. And yet, did any of the characters have any proper shading through hatching? Did any of them have any realistic features like nostrils (for the non-pig-nosed humans) or nipples? No they did not. Well… There is that tribal scene in Swallowing the Earth, but Tezuka only uses hatching to separate the black tribal people from the protagonist, who has no shading, abs, nor nipples, so it really doesn’t harm my argument. Even in the original Kamui-den, the intended “stand-out” scenes don’t really have much hatching or cross-hatching.

![]() |

| From vol.7 |

In fact, I get the feeling that even Chiba Tetsuya wasn’t quite comfortable with the big step he had taken forward, especially on the point of nostrils. In volume 2, we again see more hatching and nipples, but the nostrils disappear from any close-ups. As the series progresses, the hatching and cross-hatching get more and more detailed and the blurred spots that passed for nipples in volume 1 have now developed an areola distinct from the actual nipple. And yet, the nostrils do not reappear until volume 8 making a special exception for Rikiishi in the famous scene where he almost gives into temptation.

![]() |

| Nostrils strike back in in volume 8 and Volume 13 |

In fact, Joe doesn’t start getting nostrils again until volume 13, more than half-way in the series! It’s only from hereon that Joe’s nostrils become more and more frequent for his close-ups. Obviously, it doesn’t take much artistic skill to plot down two black spots and call it nostrils. So as trivial as this all seems, this is a conscious choice by Chiba. Just as Tezuka or Ishinomori didn’t yet feel quite comfortable giving such realism to their characters, it must have taken Chiba some time before he thought of Joe as such a human character that the nostrils were a necessity in any close-up scene meant to deliver impact. It’s also interesting to note that Youko never gets any nostrils although she tends to get more detailed eyebrows and eyelashes. Chiba does try a few times to try and place lips on her, but he quickly gives it up. Clearly, the attention to eyebrows and eyelashes are just markers of femininity, but the reasons for the lack of nostrils are less clear. It’s possible that Chiba never feels that he has a firm-enough grasp on Youko’s character to feel comfortable in giving her the same human-treatment, being a Kajiwara creation as Natsume Fusanosuke theorizes in the BS Manga episode on Tomorrow’s Joe.

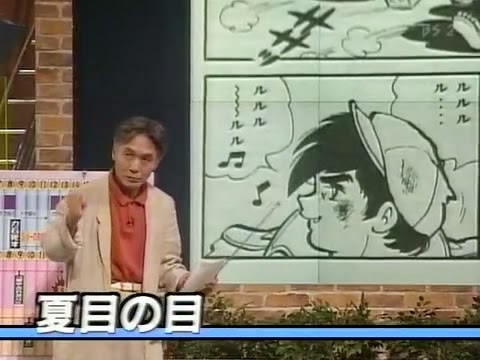

![]()

A little side-note here. In case you’re wondering, BS Manga-Yawa is a manga talk show on NHK in which a panel of manga critics and guest stars discuss a different manga for every episode. Most are entertaining and/or enlightening, especially the “Natsume’s Eye” segments, in which the distinguished manga critic Natsume Fusanosuke (incidentally, he’s the grandson of Natsume Souseki. Dayum) offers an in-depth analysis on a particular aspect. Alright then, now that I’ve talked about super-interesting nostrils and nipples, it’s time to talk about the story.

![]() |

| Character development: No hair-cuts necessary |

The thing that really impresses me about Tomorrow’s Joe every time I read it, is the gradual development of the major characters (Joe, Youko, and Tange) and how fleshed out they all seem by the end. It’s communicated quite effectively through the combined effect of the written dialogue and the visual expressions or actions.

![]() |

| Is Yabuki Joe gonna have to choke a bitch? |

Let’s start with Yabuki Joe. I absolutely love what an unruly delinquent he is. At so many points in the earlier half of the manga, he seems to almost go out of his way to be a total dick (pic most definitely related). Now some people might not like that. Probably the same group of people who’re genuinely offended by Matsutarou when watching the currently-airing anime adaptation of Chiba’s Rowdy Sumo Wrestler Matsutarou, I guess. But to me, this unrestrained wildness feels so raw that I never doubt if he’s the product of unnecessary tampering of editors, wary of over-protective parents. He’s a real delinquent through and through, not the posers you might see in some modern manga who only know how to die their hairs and steal money from the weakest-looking nerd in their classes. And yet, he’s never an “evil” character.

![]()

He beats the shit outta little kids… but mostly in self-defense and even goes out of his way to save Sachi from yakuza thugs. He’s not above stealing, vandalizing, extorting, or conning people… and yet he naively dreams of building hospitals, parks, and playgrounds for his Doya neighbourhood. He puts up a tough front and brags incessantly when confronted, but when alone, he’s usually silent and curled up in the fetal position.

He’s never black nor white (except for his ink colours). He feels… human. Like in the way he’s a loud-mouthed character who’s often bad at hiding his feelings or loves to vent out his feelings (examples above) when he’s angry, and yet when he’s feeling sullen or dejected, Kajiwara chooses to have him be reticent and the only hints to his thoughts and feelings are through Chiba’s art.

![]() |

| from v14 p187 and 190 |

These two pages are particularly good examples of that. When asked by Yoko if he had changed, Joe tries to put on an air of nonchalance and a faint smile but can’t help but sweat nervously. Youko, being the shrewd observer she is, immediately picks up on his stiff body language and on p201 (not attached above), questions him on how long he’s been battling his weight. This is, of course, all foreshadowing the troubles Joe will face in volume 19 in staying a bantamweight. Meanwhile, on p190, Joe looks visibly surprised, or at least, thrown off-balance, when he learns that Youko had only invited Carlos Rivera for his own sake. Through this, you can see that his perception of Youko is still clouded by his bias and suspicions, making a selfless and caring Youko impossible for him to imagine on his own. None of these scenes have dialogue or narration that ham-handedly gives away Joe’s thoughts, but Chiba leaves enough visual cues for the attentive reader to understand his state of mind. Yes, yes, sweat-drops may seem trite in the world of manga, but what’s effective is effective.

![]() |

| from v19 p178 and 190 |

Another good example of subtle scenes that really flesh out Joe’s character is the fantastic wedding scene in volume 19. As Noriko and Nishi walk down the aisle, Joe shouts playful jeers at Nishi. That’s classic-Joe for ya, isn’t it? Well, it’s up to your interpretation but I don’t see it that way because of the pensive look he has in p178 as shown above. If he were really just in his usual joking-mood, it’d be hard to explain why he suddenly makes such a face. The truth is, Joe already knows what Youko desperately wants to tell him at this point in the story. He knows there’s something seriously wrong with his body, whether it’s punch drunk syndrome or some other medical condition. And yet, he’s already made the choice to fight Mendoza at the cost of his life. For any man who knows his death is near, the sight of new beginnings, whether a wedding or a newborn baby, is bound to make him pensive. As Joe watches his friends marry and embark on the next phase of their lives, he can’t help but wonder, “What if? What if I didn’t walk down this path to self-destruction? What might the world hold in store for me?” It’s not that he’s getting cold-feet, but he’s merely pondering at what might have been. And in a Joe-like fashion, as soon as it’s his turn to give a toast, he puts on a nonchalant front again by giving a half-assed speech (“Welp! Have a good life!”) as if he hasn’t a care in the world in order to not share his burdens with anyone else. An example of an even better expression is Noriko’s on p190. Absolutely brilliant. If that isn’t the face of woman who’s resigned herself to her second choice (Nishi) but can’t help but ponder what a life with Joe might have been, then I must be blind.

![]() |

| Joe on the values of sportsmanship (v2 and v4) |

Equally impressive is how Joe’s wildness is handled. Too often in stories do antagonists or “bad” characters do a 180 in their personality under the guise of “character development.” [sarcasm]After all, dynamic characters are better than static characters! That’s what my English teacher said![/sarcasm] This shit pisses me off to no end. It’s all about execution. There’s no point in having a character be dynamic if you’ve essentially reduced him to two polar opposites with no in-between such that the effect is indistinguishable from having two separate flat/static characters. Joe starts off as a wild self-centered hooligan who’s not above breaking two or three rules as long as he wins in the end. If Kajiwara and Chiba were poor story-tellers, they’d follow the rule of more change = better characters, and de-fang Joe into a self-less goody two-shoes. It’d make no internal-logical sense for such a deformed Joe to be so stubbornly determined about a self-destructive showdown with Mendoza. Thankfully, Kajiwara and Chiba wisely chose not to cut down on his wildness but merely redirect it.

![]() |

| A dramatic monologue from v2, though unfortunately not done justice in the English translation |

Joe in the beginning was wild because it was an expression of his freedom, the only thing he possessed in the world, having no money, home, family, or friends. But as the story progresses, he acquires all these things. He earns money from his matches and lives in the gym, while Tange (despite his gender, he comes across as more of a mother than a father-figure to Joe), Nishi, the kids, and the rest of the Doya-folk become the first family and friends he’s ever had. But above all, Joe finally finds a meaningful purpose in life for the first time. He redirects all his energy from his former hoolig into beating Rikiishi. His wildness, which had fed off their rivalry, naturally withers away in the immediate aftermath of Rikiishi’s death. Joe is no longer capable of using the no-guard stance and famed cross-counters that epitomized his 100% offence-minded wildness. When he finds a new purpose in life (seeing how much he measures up against Carlos), he’s able to shake off the mental trauma and return to being “Brawler Joe.” And yet, he’s not the exact same boxer he once was. He no longer purely relies on counters even though he can still throw them, and the commentators note his defensive techniques are much better. This makes sense in the context of a boxer naturally adding more options to his arsenal with time, but it also makes sense in the context of his new-found purpose. His goal is no longer to fight a single person, as it had been in the arcs leading up to the fights against Rikiishi or Carlos.

![]() |

| Joe’s new-found purpose in life (v14, v20) |

His new purpose is to taste that intense burning sensation gained from proving his worth on the ring, even if that entails burning up into nothing but white ashes. He’s no longer willing to break any rules on the ring because that would be to compromise his goal, depreciate his worth, and signify he’s a lesser boxer.

![]() |

| After the fight with Harimau in v19 |

This is precisely why he never resorts to any penalties in his fight against Harimau, no matter how many penalties Harimau rack up. He’s still a wild boxer and his animal-like instincts attest to that in the final showdown against Mendoza, but his coarse wildness has been paradoxically tamed or polished, by his purpose in life.

![]() |

| Youko’s first appearance, beginning of v2 |

After Joe, my second favourite character in the story is Youko. I love her because how she starts out as a total mystery and her character is only slowly revealed as the series progresses. Take for example, her first appearance which was at Joe’s trial. She only has a few lines and her almost unchanging expression make it difficult to gauge her intentions. Is she there to gloat at Joe? Or is she there simply to make sure the trial proceeds smoothly? Joe on v2 p22 seems to think the former but just how reliable are his opinions? After all, it’s possible that he’s biased against the rich and privileged due to his poor background.

![]() |

| re-translated from c22 (v2 p221) |

I certainly think there’s enough evidence in the manga for a definite answer. The fact that she stops showing up periodically to juvie after Rikiishi leaves seems to confirm Joe’s suspicions and that she was never staging plays out of any genuine concern for the “pitiable rabble.”But I don’t think you need to wait for that comment in v5 for confirmation of Joe’s suspicions. There’s enough material to analyze in the scene where Joe responds to Youko’s demands to know why he thought she was unfit to play Esmeralda. This is one of two scenes in the manga that Youko yells in anger. Considering how restrained and composed Youko usually is, most likely a product of her almost aristocratic-upbringing, it’s not unreasonable to conclude that Joe’s remarks hit her too close to home. The way Chiba marks a slight blush mark in that bottom left panel seems to hint at her embarrassment from being exposed. It’s because she feels that she’s been exposed that she wants to get even with Joe, but she can’t just let Rikiishi pummel him there and then. After all, that would only cause problems for Rikiishi, whom she cares for, and she might also fear that allowing such a direct retaliation would be to admit Joe’s accusations as true. And so she seeks a by-the-books way at getting back at Joe, as to not tarnish her image in front of the large crowd gazing intently at that scene; hence, she enthusiastically accepts the boxing match proposal.

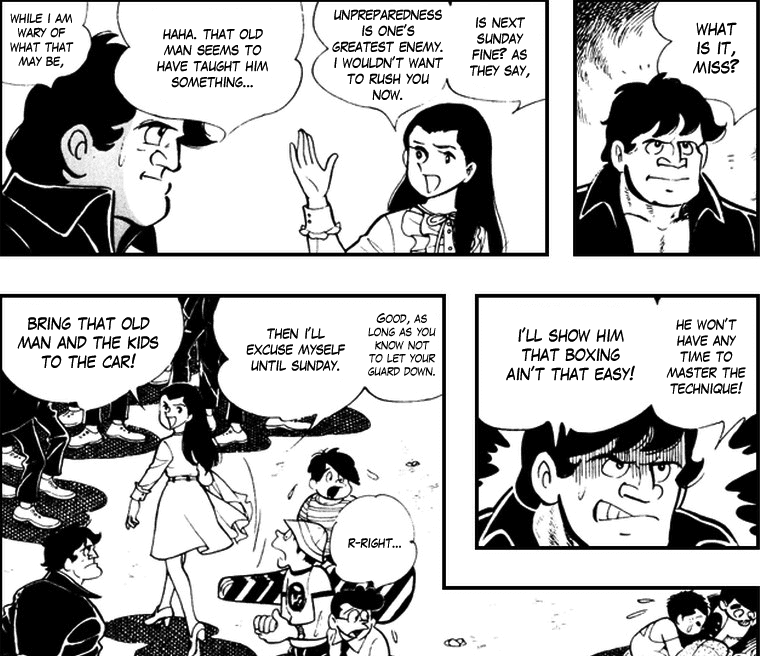

![]()

In the chapter right after that, she leaves the detention facility after confirming the date of the match with Rikiishi. When I look at the expression of her face as she abruptly leaves and the general tone of her lines on this page, I can’t help but feel that her confirmation of the date with Rikiishi has less to do with her concern over the possibly of Rikiishi getting hurt, and more with the possibility of her failing to get back at Joe. That line, “Good, as long as you know not to let your guard down” just seems to convey a tone of, “Good, you better win.”

This conflict between her immature desire to get back at Joe and her concern for her image is also captured in this scene, when she has no qualms stooping down to Joe’s level and throwing dirt at him only when none of the other juvie inmates or guards are watching.

![]() |

| Separated at birth!? Dun-dun-duuunnn! |

Now if my interpretations are making it sound like she’s not the quiet-spoken, composed, and graceful aristocrat she tries to appear as, then you’re understanding me correctly. I personally believe that despite surface-dissimilarities, Yabuki and Youko are far more alike than any other character in the story, though neither would be willing to admit that (humorously enough, they look almost identical at the start of the story, but that’s probably unintentional). Now you might be saying, “Wait, wait, wait. What about Rikiishi? Surely, Joe’s greatest friend and rival shares a lot more in common with Joe than Youko.” I disagree and I point to you this page below.

![]() |

| v7, p166 |

Rikiishi states in no uncertain terms here that his ambition is to become rich, famous, and the proud owner of pacific and world title-belts. This is fundamentally different from Joe. Joe never fights to become rich or famous and he certainly doesn’t fight because he wants some title-belt. He fights because, as I mentioned above, he revels in that intense burning sensation gained from proving his worth on the ring, even if that entails burning up into nothing but ashes. This is why he doesn’t care about the result of any fight in which he felt this burning sensation. Go back to when he lost to Rikiishi in their ultimate showdown in v8. Immediately after the loss (before Rikiishi dies), what’s the first thing Joe does? He walks up with a smile and concedes defeat. What about the first fight with Carlos when he loses by disqualification because of Tange’s mistake? Again, he’s not angry. He feels refreshed that he’s finally beaten off Rikiishi’s ghost. What about the second fight with Carlos? Does he care that his chance at entering the world-rankings was foiled because of the double-disqualification? No, he couldn’t have been more satisfied to have fought with Carlos, both fighters baring all they had, whether illegal or legal techniques. And last but not least, what about the world-title match with Mendoza? Does he care that he lost? Or if you fall into the faction that believes Joe had passed on even before he heard the final decision, do his actions or attitude immediately after the final round show eager anticipation of what the result was? Of course not. He literally states during the match that all he wishes is to burn into white ashes. That’s all he desires. As he states in the last page of volume 19, he must go on the ring because the world’s strongest man is waiting for him. Not because he has a chance to win the world-title. The world-title, or any title for that matter, is meaningless to Joe. Plus, there’s the fact that the usually calm and mild-mannered Rikiishi has a personality that’s almost a polar opposite from Joe’s.

![]() |

| c23 (v3 p11) |

So let’s return to Youko. I’ve already explained how she actually possesses an immature and selfish streak, just like Joe, but that alone isn’t what I’m basing my theory on. The main reason why I think Yabuki and Youko are reflections of each other is in their goals, their pursuit for “tomorrow.” The only characters who reference the entire theme of this manga, the pursuit for tomorrow, is Joe, Tange, and Youko. In the above scene, Youko uncharacteristically forgets that there are others around her and without realizing it, she babbles out loud (this is no thought-bubble) about the meaning of tomorrow. Why? Because again, this scene has hit her too close to home. She isn’t just describing Tange and Joe’s arduous pursuit for tomorrow. She’s describing her own self. At the start of the series, I think that Youko, like Joe, doesn’t have any clear goal of what to do with her life. She’s playing the part of the wealthy philanthropist in an attempt to gain some sort of meaning for her life by exchanging money for respect and a sense of moral fulfillment. However, just as Joe’s chance encounter with Rikiishi changes his life, so too does Youko’s life when she meets Joe. Her fixation on Joe is hinted at several points in the manga leading up to Rikiishi’s death.

![]() |

| Tsun-tsun |

Another good example follows shortly after this scene in which she sends Joe a congratulatory bouquet and letter, hand-written to boot, after his first win as a pro-boxer (v6 p214). When questioned by Rikiishi, she tries to hide her feelings by saying they were funeral flowers for when Rikiishi crushes him, to which Rikiishi wryly responds that they’re far too flashy for a funeral.

![]() |

| v10 p130-131 |

If you don’t think Youko is fixated on Joe, then it’s difficult to explain how she, a relative novice to the world of boxing, can immediately tell that Joe’s a mere husk of his former self in his comeback-match in v10, something that even the veteran commentators are incapable of doing. Her fixation is undeniable by v10 p130-131 when she decides to become the new manager of Shiraki Gym all in order to help Joe recover his form.

![]() |

| stepping into a man’s world |

Now this is a difficult path that Youko’s chosen for herself. Numerous times, the story reiterates how the world of boxing is exclusive to men. The other gym managers point fingers behind her back, and the press seems to think of her and her actions as the “random whims of a rich lady.” Her situation is comparable to Tange, who’s also mocked by the other gym managers and seen as bit of a loony by the press. Look back to the image I posted above from c23 (v3 p11). “A today in which you suffer mockery from others who treat you as crazy… If and only if such a today exists, then… Then will a true tomorrow… A true tomorrow-” Sound a little similar? It’s not just her situation that’s similar to Tange. From v10, she basically assumes the role of a second Tange, working covertly from the shadows to support Joe.

![]()

Now when I call her a second Tange, you might be thinking, “Then wouldn’t Tange be the better candidate? Wouldn’t he be the one who shares most in common with Joe than any other character?” Setting aside the obvious problem of their polar personalities, the real reason why Tange can’t be viewed as a reflection of Joe in any way is that he’s far too soft-hearted. He tries his best to aim for tomorrow but his growing attachment to Joe, whom he comes to think of like his own son, means that he has too much to sacrifice for tomorrow. He essentially becomes a man complacent with “today.” This is evidenced numerous times throughout the manga such as all the times when Tange, fearful of his player’s health, tries to convince Joe to forfeit a tough match. In volume 11, Tange even decides to close the gym in order to prevent Joe from destroying his self.

![]() |

| Yokokura, an alternate Tange |

Now compare that to Youko’s actions as Joe’s unofficial manager. She’s not afraid to bring a monstrously strong opponent over like Carlos Rivera for Joe’s sake, fully knowing that if her plan backfires, Joe would not only remain psychologically traumatized, but crippled as well. Her sink-or-swim methods stand in stark contrast with Tange’s coddling. She’s not afraid to jeopardize the lives of other boxers like Tiger, Harajima, Nangou, and most famously, Takigawa Shuuhei. In v18, Kajiwara sets up Takigawa’s coach Yokokura as Tange’s alternate-self of sorts. Both were poor and unsuccessful gym owners who took massive loans to keep their gyms running in the slim hopes that they’d be blessed with a “golden egg” one day. Tange even weeps in sympathy at Yokokura’s tears of joy broadcasted on television. Of course, Takigawa Shuuhei might seem more of a silver egg in comparison to Joe, he is everything to Yokokura nonetheless. And yet, Yoko does not blink twice in breaking this silver egg all for Joe’s sake.

![]() |

| Tange and Youko’s two choices |

But the most critical difference between Tange and Youko comes in the final volume. When Joe’s luck and energy seems to run dry, and all those watching are painfully aware of the hopeless situation, Tange cannot bring himself to give a willing approval to his player’s almost insane insistence on continuing the fight. However, in comes Youko. She alone tells Yabuki that he must fight with no regrets and that she’ll stand right by him watching every last moment, even though this means she’ll be watching the love of her life as he dies or becomes irreversibly crippled.

![]()

Yes, she’s been the timid woman who couldn’t help but avert her gaze every time Joe received a severe beating. Yes, she, like Tange, also tried to convince Joe to retire on a few occasions. She also tried to run away from watching his matches on 3 separate occasions. And yet, in the very last match when Joe needs support the most, it is Youko who gives it to him. She is the one willing to sacrifice both her tomorrow for the sake of Joe’s tomorrow. Or perhaps, it’s more accurate to say that her tomorrow was Joe’s tomorrow all along. This resolve of hers is why at the end of the manga, Joe hands his gloves to Youko, not Tange or anybody else. It is not an expression of pity or Joe returning her love. It is to signify him acknowledging her as his comrade, the only one remaining who understood the tomorrow he aimed for.

![]() |

| Quite possibly the most iconic ending of all time in manga |

Now a word about the ending. I’ve seen a lot of people say that Joe dies at the ending, and even people who’ve yet to read/watch Tomorrow’s Joe will usually have heard that he dies at the end. I want to point out that this is not quite the case. The fact that he turned white just like burnt ashes does not necessarily correlate to his death, although it is quite tempting to think so. This ending is purposely meant to be an ambiguous ending. The only thing definite about the ending is that Joe loses the match and whether he dies or not, is up to the reader’s own choice. Particularly telling about this issue is the original ending as envisioned by Kajiwara Ikki.

![]() |

| The original end for Tomorrow’s Joe |

In this version, Mendoza wins by a narrow decision and Joe is slumped on the chair, drained of all his energy. Now here’s where it diverges from the actual ending. Tange then tells him that he may have lost the match, but he won the fight (おまえは試合には負けたが、ケンカには勝ったんだ). The scene then switches to the terrace at Shiraki’s mansion. Joe is idly sitting by with his arms locked around his knees as usual while Youko tenderly gazes at him. Chiba Tetsuya didn’t quite feel comfortable with this ending and asked Kajiwara Ikki if he could change the ending. Kajiwara, busy with many other serializations and trusting Chiba’s ability, gave him free reign to change the ending as he saw fit. However, as the deadline approached, Chiba couldn’t come up with an ending he liked. It was during this dilemma that his editor pointed out the time Joe and Noriko went on a date for the first time. Upon remembering the burning into white ashes line, he immediately drew the ending we’re now all so familiar with. As you can see, Chiba’s major change to the ending was not to kill off Joe. It was to give the readers a more easily understandable resolution to his purpose in life. Although I don’t have any official interview transcripts (so take this with a grain of salt), I have heard that at one interview later on in his life, one audience member asked Chiba why he killed off Joe. To this, he responded that Joe did not die that day because he is Tomorrow’s Joe. This echoes Natsume Fusanosuke’s own interpretation of the ending, in which he points out that the left-side in manga represents the future in manga (right-to-left order, remember). By having Joe sit down facing the left with a faint smile, while the status of his mortality is kept intentionally ambiguous, the manga tells us that whether or not he died is trivial. The true significance is that Yabuki Joe faces tomorrow.

![]()

In any case, Kajiwara Ikki’s hugely influential sports trinity of the late ’60s (Star of the Giants, Tomorrow’s Joe, Tiger Mask), transformed Weekly Shounen Magazine from something read by only kids into acceptable reading material for college students. While the main characters Hyuuma and Tiger Mask of Star of the Giants and Tiger Maskwere popular, it was particularly Yabuki Joe that many Dankai youths who participated in the student protests of the ’60s identified with. The fact that he’s called a “golden egg” at several points only served to make him more identifiable. Golden Egg (Kin no Tamago) was a popular term in the ’60s for the Dankai youths who worked blue-collar jobs and served as the metaphorical golden egg which supported the rapid economic-rise of the ’60s. This is why when the Japanese Red Army, a communist militant group, hijacked JAL Flight 351, they famously announced, “We are Tomorrow’s Joe!” New-found prosperity, passionate youths seeking to change tomorrow, a flourishing gekiga movement… This is the necessary context a manga like Tomorrow’s Joe is best judged under. Many manga critics have followed this model, and there’s even one book which gives precise real-life dates to Yabuki Joe’s life in an attempt to firmly frame Tomorrow’s Joe as a story of the Dankai Generation. Nevertheless, more than 20 years have passed since the first chapter of Tomorrow’s Joe was serialized before I was born and more than 40 years have passed since I began translating this manga into English. Lack of context nor the generational gap did not dull my appreciation of this manga when I was first exposed to it, as I’m sure is the case for many other manga fans around the world, regardless of how many years after we were born after its serialization. This is the surest sign of that often ambiguous but coveted term “classic,” and I sincerely hope that these unofficial translations may help in preserving its memory.

+%EF%BD%A2%E3%81%82%E3%81%97%E3%81%9F%E3%81%AE%E3%82%B8%E3%83%A7%E3%83%BC%E3%80%8D+%E9%AB%98%E6%A3%AE%E6%9C%9D%E9%9B%84%EF%BC%8F%E3%81%A1%E3%81%B0%E3%81%A6%E3%81%A4%E3%82%84+(2001-08-06)+%5B59m59s+480x360+29.97fps+H.264%5D.mp4_snapshot_24.15_%5B2014.04.26_06.51.39%5D.jpg)